When you go to a traditional Czech restaurant or a cafe and study their menu, you may find a list of coffee-based beverages you have never heard of before. The most intriguing ones include Vienna Coffee (coffee with whipped cream), Algerian Coffee (coffee with whipped cream and egg liquor) and Turkish Coffee (coffee with ground coffee at the bottom of the cup). Should you order a presso, expect something like lungo, and if you want to experiment with a piccolo, you might end up with a plain espresso but also a ristretto.

Czech coffee lovers have had it with the inconsistencies in coffee terminology and typology. In 2010, a coffee consultancy called Kávový klub (Coffee Club), was founded “as a response to the need to promote knowledge about fine preparation of coffee in cafes as well as at homes in the Czech Republic.” They launched a popular campaign called “Piccolo does not exist” with the ambition to eradicate piccolo as well as other instances of “nonsense” and establish a new coffee order.

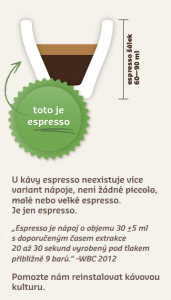

There is no such thing as piccolo, they say.

“There is no variation to espresso, there is no piccolo, no small or large espresso. There is only espresso. The volume of an espresso is 30 ± 5 ml, the recommended extraction time is 20 to 30 seconds and the pressure it is made under is approximately 9 bar. –WBC 2012 Help us reinstate a coffee culture.”

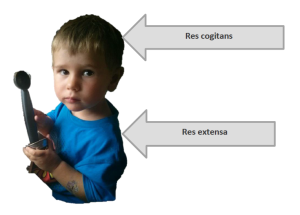

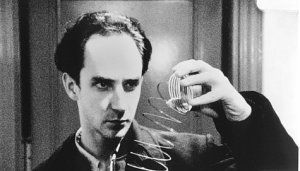

Seeing their poster for the first time, I immediately thought of Magritte’s picture of a pipe that says “This is not a pipe”. Magritte’s picture is witty and unsettling and makes one reflect on the relationship between a physical object and its representation. The campaign’s depiction of what is an espresso lacks that kind of sophistication as it defines espresso in an authoritative and normative way. The interesting part is that it unintentionally invites a viewer to experience a dissonance between knowledge, language and the perceived world of things: what we know and how we talk about it does not necessarily correspond to our experience. (If I’ve already seen, ordered and drank something called piccolo, it exists, but what if it actually was an espresso?) Campaign organizers should not be surprised at how many people now jokingly (yet proudly) demand piccolos or even consciously offer them to guests. Partially, perhaps, it is simply because our brain has trouble processing negative declarative statements, such as the notorious “Do not imagine a pink elephant!” But the issue is more complex.

For a long time, anthropologists have been dealing with a similar problem: how to study phenomena such as spirits and spirit possession without applying our own bias. Just because western science cannot prove the existence of spirits, we cannot assume that a non-western person possessed by a spirit should be regarded as psychotic. Consider the Hauka movement in Niger, which was documented by the French ethnologist Jean Rouch in a short documentary called Mad Masters (Les maîtres fous, 1955). The members became possessed by British Colonial administrators and, while in trance, mimicked some of their ceremonies. (You can watch the video on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gUilOCTqPC4 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c8FR85eR-ec.)

Anthropologists have tried to study and understand the world, rendering importance to all kinds of knowledge and beliefs. To do that, they needed to question their own tools, methods and biases and devote themselves to giving voice to all forms of life, belief, and knowledge, especially the endangered ones – even if they are as tiny as a piccolo (which means small) .

Interestingly, I found a piccolo in East London and here’s what the “natives” are saying about it:

More documentation of piccolo. By the way, does machiato exist or is it macchiato?